Skepticism, and the Inherent Fear Simmering Beneath its Surface

Or, on our bewildering fetishization of doubt

“Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence” — Carl Sagan

I used to pay very close attention to the topic of UFOs (now “UAP”). I don’t devote much energy to it anymore (though it remains utterly fascinating), but what I do still think about often is the condescension levied against people who study unconventional topics, be it UFOs, spiritual mysticism, or anything else in that realm.

That Sagan quote is one self-branded skeptics often point to as a golden rule of reality. It’s my opinion that this quote, while perfectly sensible on the surface, is so often interpreted frivolously in ways that not only contradict the concept of science, but also seem indicative of some degree of deeply ingrained unconscious fear.

I’ll explain. If you arbitrarily hold “extraordinary” claims to a higher standard of proof than those comfortably under the umbrella of the status quo then all you’re effectively doing, whether intentionally or not, is taking steps to exclude anything “extraordinary” from entering your life. Isn’t this kind of an objectively non-curious way to live? Perhaps we could amend that Sagan quote to better represent the way I feel it’s often deployed: “extraordinary claims that scare me require extraordinary more evidence than I will ever accept.” Because I think, if we’re being honest with ourselves, this is what it’s often actually about.

The Spectrum of Fear

The best example of this attitude I can think of is Michael Shermer, the founding publisher of Skeptic magazine, and his particular brand of reactionary doubt. Shermer seems to understand, whether consciously or unconsciously, that his audience is made up of individuals living in some degree of fear and/or anxiety. I do not mean fear as a pejorative here, nor do I mean any disrespect to Shermer, who is by all accounts a brilliant thinker and communicator. I’m picking on him precisely because I recognize his skills, not to spite them.

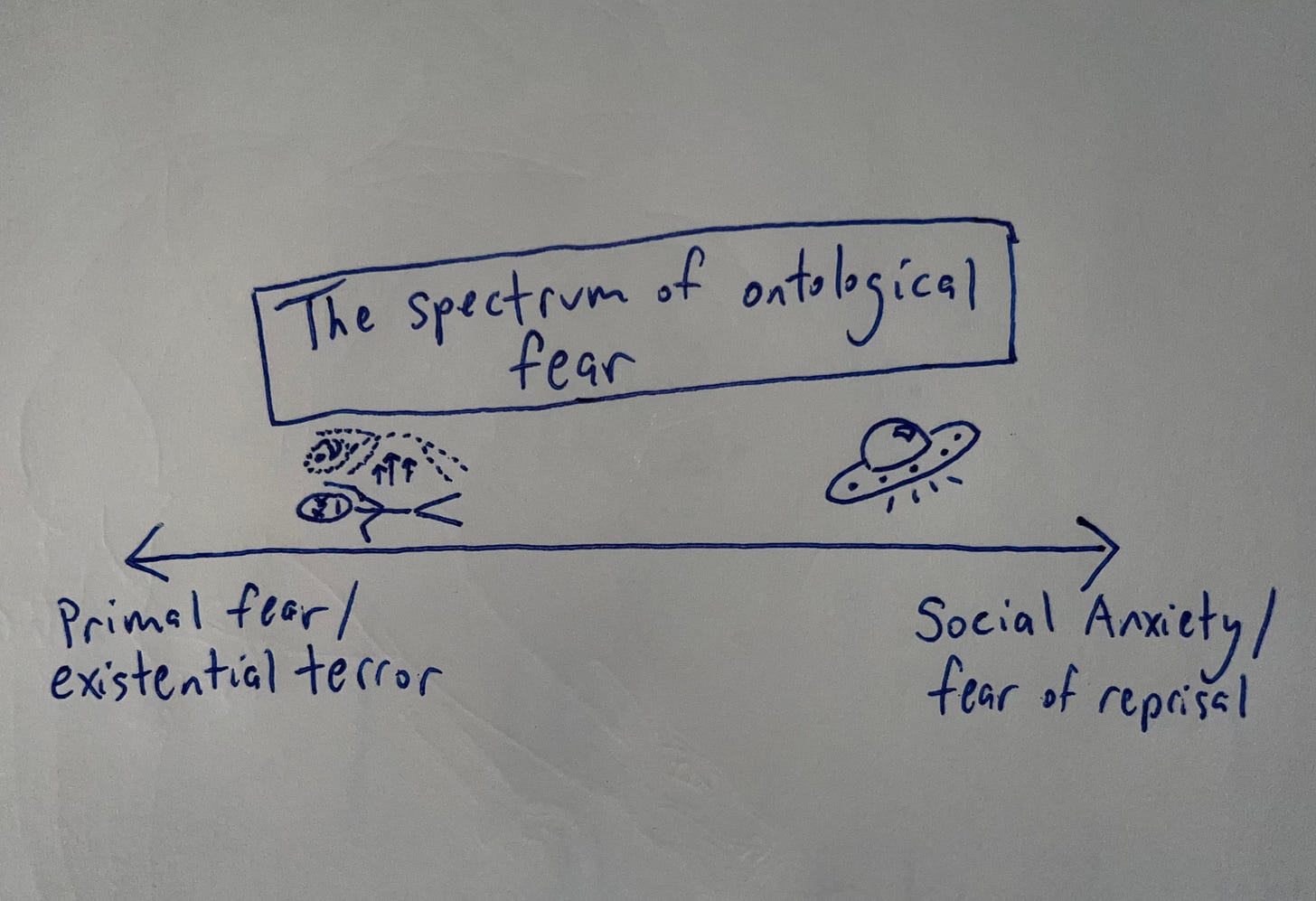

Still, the point remains, and this fear to which I’m referring in his audience might best be portrayed as a spectrum.

One end of this fear spectrum would constitute a direct phobia of the unknown. To revisit the context of UFOs, this might manifest as a fear of the topic’s implications for humanity with regard to concepts like our position in the cosmic food chain, abductions, attacks, stuff like that. To be clear, I consider fear to be a perfectly valid emotion to experience when faced with huge philosophical paradigm shifts like this, but that doesn’t make it helpful—fear so rarely is.

The other end of the spectrum might represent something more akin to social anxiety, which arises when the concept being considered does resonate with the individual, but they don’t want to engage too closely with it for fear of experiencing firsthand the stigma inevitably attached to those who engage with the topic in a serious (i.e., non-ironic) way.

Regardless of where one may fall on this theoretical spectrum, a perfectly logical response to this fear (whether of personal injury or social reprisal) may be to seek out a certain type of refuting ideology to assuage it—enter skepticism. The Michael Shermers of the world might therefore be considered champions of the ontologically anxious, carrying the torch for those who don’t yet feel ready to explore certain deeper aspects of reality (or, more likely, their own pscyhe).

Some Caveats (i.e., Keeping Myself in Check)

To be clear, I am conscious of the fact that fear is not the only reason one might be motivated to seek alternate explanations for any given phenomenon. Indeed, it could just as easily be framed as a zealous pursuit of truth, which is an objectively good thing. Consider a cancer patient hunting for a 2nd opinion on their prognosis. Might they be genuinely seeking a clearer understanding of their situation, and searching for the best possible path forward? Hopefully that’s exactly what they’re doing. The key, for our purposes, would lie in how that patient then responds to the new opinion, assuming they’re able to secure some better news somewhere. Do they critically compare the merit of each opinion? Or do they immediately choose the path which makes them feel better in the moment?

(Admittedly this isn’t a perfect metaphor. In fact, in the case of this hypothetical cancer patient, because of the profound psychosomatic power of the “placebo effect,” I might actually recommend they do blindly pursue the better-feeling route, no matter its validity. But you get the point.)

Additionally, fear is nothing to be inherently ashamed of—we all feel it. For example, I’m often terrified of my own psyche, but it’s exactly this fear which motivates me to explore it further. This could be considered either bravery or stupidity, depending on your perspective, but in either case it pushes me forward toward what feels like growth. So when those in fear use the guise of “skepticism” to discredit all the bold, shameless dorks (said with love) staring these big questions in the eye, I’m of the opinion that it actively stunts our collective growth.

The Universality of Skepticism

One thing worth pointing out is that we’re all skeptical. This thing we call “skepticism” is arguably a key part of the way our brains process the world. The brain’s entire evolutionary/biological function is essentially to convert sensory input into a tangible and navigable reality, all while minimizing the potential for surprise to the best of its ability. The neurological framework known as predictive processing describes this function quite well. In it, the brain’s emphasis on minimizing surprise is referred to as “error reduction.”

For example, suppose you’re walking down the street and encounter a dog with a coat of vibrant pink fur with yellow polka dots. One conceivable reaction you might have to this scenario could be the belief that you’ve discovered a brand new species of dog. But another, much more likely reaction, would be to ask yourself a question along the lines of “who spray painted this dog?”

This is the more likely reaction because your worldview, up to that point, obviously didn’t include a candy-painted species of canine, therefore your brain activated its skeptical regions in order to reconcile the problem of how that particular dog’s fur color came to be, and the result was a hastily formed hypothesis involving spray paint (which could then, if the individual so desired, be tested “scientifically,” perhaps by asking the dog’s owner about the nature of the colorful coat).

This whole concept is what the widely-revered psychoanalyst Jean Piaget referred to as the interplay of schemata, assimilation, and accommodation. And if you identified more with the second option (“who painted this dog?”) then congratulations! You’re a skeptic- that’s skepticism in action.

In this model, “skepticism” is the filter through which sensory information must travel before finding its proper place in our accepted psychological realities. This is why I find it strange when people take pride in skepticism, touting it as an almost noble quality. Being skeptical isn’t some sort of achievement—it’s a basic neurological function that literally everyone has. There are so, so many things that make you special…but being a “skeptic” is not one of them.

Open your Heart > Open your Mind

Maybe the most interesting thing about skepticism is that, as a byproduct of all this neurological machinery, it also has deep roots in the feelings portions of the psyche. Doesn’t that feel sort of counterintuitive? After all, if we’re talking about skepticism we’re usually talking about intellectualism, so you might think the whole thing would be an intellectual process. That’s what I used to think anyway.

So when it came to the topic of UFOs, I’d always over-prepare and speak obnoxiously fast during conversations—I wanted to present as much information as I could, as quickly as possible. I thought this made me appear “rational” but in hindsight I now realize the effect was much closer to “raving lunatic.” Whoops. In other words, my goal was always to appeal to my audience’s logical thinking processes, because that’s where I thought the magic happened. Turns out it goes much deeper than that.

Low Road/High Road

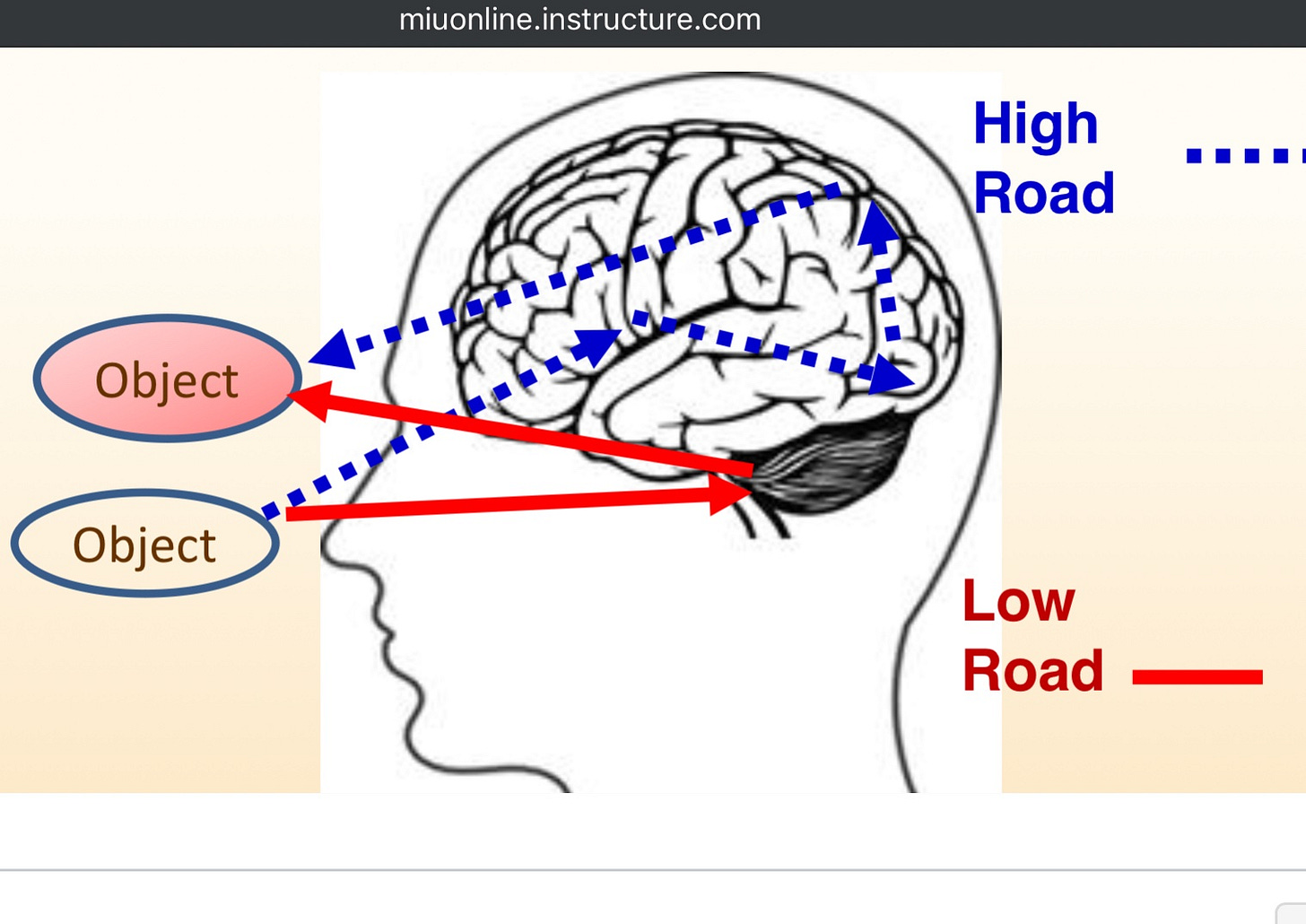

My neuroscience professor, Dr. Fred Travis, a brilliant researcher (and incredibly sweet man), describes the brain as having a “low road” and a “high road”—the diagram above is a screenshot from one of his lectures—which I’ll quickly explain because it helps make sense of all this.

The low road is the realm of kneejerk reactions, which is actually where the phrase “kneejerk” comes from. That is, when a doctor bangs your knee with one of those rubber mallets and you instinctively kick the glasses off his face, that’s the low road in action. It’s an immediate stress response which requires no thinking. Imagine you’re walking down the road and suddenly, as a practical joke, somebody jumps out from behind a bush and yells at you. Your low road response will almost certainly trigger—you might even throw a punch at them. Cue the wisdom of J. Walter Weatherman.

The high road, as you might expect, is the road toward higher logical reasoning. This happens in the frontal lobe (right behind your forehead)—however, if you look at that diagram again, you’ll see that even the road toward the frontal lobe must first pass through the back regions of the brain, where we process emotion and sensory inputs. This means, no matter what, your response to any observation you’ll ever make starts as a feeling, which is then retroactively rationalized by your higher intellect. Something to keep in mind when you take a firm oppositional stance to anything—are you taking that position as a genuine assertion of rational truth, or are you succumbing to an emotional response? The line between the two is shockingly blurry, just like in our cancer patient example from earlier.

I have a pet theory, which I won’t go into here but will probably write at length about in the future, that every time we face an idea which threatens our worldview we immediately slip into the 5 stages of grief: That is, Denial → Anger → Bargaining → Depression → Acceptance. I think what we call denial in the grief framework is essentially the same thing as the retroactive rationalization we just discussed. So if the information being considered causes a negative emotional response, that’ll trigger denial and the process ends as quickly as it started. But when it manages to slip past denial, that’s when it can evolve into anger, bargaining, or depression, which is where my little theory gets juicy—but like I said, I’ll write about that some other time.

Back to UFOs, Why Not

Since I’ve been flirting with the topic anyway I’ll close with a UFO story. This anecdote comes from Daniel Sheehan, the constitutional lawyer famous for litigating Iran-Contra, the Pentagon Papers, and the Karen Silkwood case. He currently runs an organization called the New Paradigm Institute, through which he assists in navigating the topic of UFOs through the halls of Congress.

If I’m remembering correctly, the story goes that Sheehan once, for some reason, found himself on a flight with a group of scientists on a plane flying north near Greenland. At some point the pilots looked down and saw strange lights down by the surface of the Atlantic. Suddenly the lights shot up to match their aircraft’s altitude, coming to rest directly in their flight path. The pilots quickly nosed down to avoid a midair collision. Upon doing so, the lights moved off to the side of the plane, now matching its speed. With the situation somewhat stabilized, and understanding that an abrupt nosedive can be upsetting to passengers, one of the pilots left the cockpit to check on the scientists in the cabin, and he encountered a pretty funny scene.

Of the, I think it was eleven scientists onboard, ten of them were glued to the windows on one side of the cabin staring in awe at the mysterious lights/crafts/whatever-they-were floating there. The eleventh remained standing in the aisle with his arms folded and a scowl adorning his face. The pilot first checked if he was okay after the nosedive, and then asked excitedly “do you see that? Isn’t it incredible?” To which the man responded “I’m a scientist, I don’t believe in those things, I’m not looking.”

I beg you, if you can help it…don’t be that guy.